Freedom in the time of coronavirus

Date- September 29th, 2020

Written by George Balarezo, Intrepid Global Citizen

10, 20, 40, 80. It was February 22nd, 2020, and I suddenly transplanted myself back to my university calculus class as I sat in a Nairobi guesthouse keeping a close eye on the sequence. Exponential growth meant the numbers would become out of control in only a few short weeks. My friends in South Korea had told me not to come back. “Stay where you are! Kenya is much safer for you and the university semester has been delayed for two weeks.” CNN and Al Jazeera screamed the same message. “South Korea is about to blow up into a deadly virus incubation center.”

Although I am very cynical about the mass media’s underlying intentions, advice from people on the ground threw my mind into a mental sparring match. I deliberated for several days while resting up from a month of dodging lions, elephants, and buffaloes, and battling sandy wind storms in the Kenya’s Turkana province. Return to Korea and dodge a virus? Stay in Kenya and ride it out while riding it out on my bike for two more weeks? I was free to make my decision, but my mind was a whirlwind of chaos.

Something told me I needed to go back. South Korea was not simply a place where I live, it was a place I referred to as home. I missed my life in South Korea too much and was willing to barricade myself in my tiny studio apartment for a few weeks. It didn’t seem like such a terrible option as I needed rest after cycling across Kenya for over one month. I had projects to work on, classes to prepare for, and friends to share stories with. As long as I had my apartment floor to sleep and meditate, an Internet connection to continue my travel writing, and a market full of fresh produce a ten-minute bicycle ride away all would be well, right?

I boxed up my bike and got on the plane. Usually, I feel relaxed, refreshed, and reinvigorated on the ride back to Korea after my cycling trips. Now my heart thumped, my breathing became short and uncontrollable, and my mind wandered into visions of horror. What am I doing? I was in a perfectly safe place, sunny and warm with friendly people everywhere and delicious equatorial fruits and vegetables spouting out of the ground all around me. Now I was about to walk into a burning building with no protection!

But I did have protection. A single KF-94 mask, one that I had used frequently in Seoul to combat air pollution. I had stowed it away in my bag for sun protection. I intended to cover my face on sunny days in Kenya instead of lathering myself up with chemical-ridden sunscreen. It was one of a rather elaborate mask collection I had at my disposal in my apartment in Seoul, and I grabbed it at the last second before leaving for the airport. It was still fresh and ready to protect me from viruses and germs.

I sat calmly at the airport with my mask hugging my cheeks and chin, but this wasn’t simply a quick trip over a few mountains and lakes, this was a twelve-hour cross-continental journey from Nairobi to Seoul. Planes are notorious for having poor air circulation and taxing your body through high altitude radiation, so I braced myself by swallowing extra zinc supplements and chomping on extra servings of spinach and mangoes moments before boarding.

As I made my way down the economy class cabin aisle, my hopes of an empty plane were thwarted as people kept piling in. They weren’t simply passengers either. They were all super spreaders. My eyes twitched in agony. Each sneeze, cough, and speck of flying saliva transformed me into an enraged beast ready to wring necks and throw fists. All compassion left me. Virus vision and germ detecting auditory powers enhanced, each bodily function had me twisting my neck to fire another nasal-flaring stare in a passive-aggressive punishment. Toddlers and mothers. Hunched over wrinkled men. Lean and energetic teenagers. They all became victims of my passive-aggressive facial expressions. Verbal communication was rendered useless as we didn’t share a common language. All I had were my piercing eyes of rage. My mind was in a completely reactive state, all freedom lost.

Each second became worse and worse. The more people boarded the plane, the more frequent became the horrible sounds of bodily functions gone completely wrong. I had visions of sprinting into the bathroom and force-covering their mouths with toilet paper. I had to do it now! Pretty soon the washroom would become the most contaminated place on the plane. How was I supposed to hold it for twelve hours?

Many people boarded the plane that day from a variety of places in the world. I am ashamed to say my mind reverted to the simplest path possible, one of discrimination. I became the very person I complained about and loathed. All of my world travel and stereotype shattering became undone in a few seconds. I scanned the plane for anyone of East Asian descent and told myself I needed to distance myself physically from them before the term “physical distancing” ever hit the airwaves. Africans safe. Caucasians safe. South Asians safe. Chinese, Japanese, Koreans? Stay away. Especially Chinese. I prayed that non-Chinese people would fill the surrounding seats.

On second thought, this wasn’t racial discrimination at all, it was “potentially infected people discrimination.” I love my friends in South Korea. I want nothing but health and happiness for my South Korean students. But more than anything, I wanted to stay away from those who were the most likely to be infected with the virus. If you had told me that people over the age of ninety years old were super spreaders, I would have sprinted in horror at the sight of cookie-baking, sweater-sewing grandmothers. If you would have told me that people with shaved heads were spreading the virus, I would have cringed in terror if His Holiness The Dalai Lama joined me on the plane that day, no matter how much peace and bliss was radiating from his soft smile.

I knew at the intellectual level that the likelihood of someone from Korea infecting me was extremely low. Out of a population of 50 million, only several hundred were confirmed cases. Actually, it wasn’t the number of confirmed cases I was afraid of; it was exponential growth. I was afraid of the unknown. How many people were actually infected in South Korea? What was the fatality rate? In late February, no one could answer those questions. I wished I had cut all my university math classes. Knowledge paralyzed my higher-order thinking and left me in a state of frenzy. All freedom lost.

My mind turned into a wild animal and I needed to calm it down. I sat in my seat and closed my eyes. A few rounds of controlled breathing through my mask slowed my heartbeat. My eyes slid shut and my nose finally stopped twitching. The tension in my arms and shoulders dissipated, and I became a fragile lump of mass. I dozed off for a few minutes before a woman’s handbag jabbed my forearm, spearing back into the conscience world. I reminded myself that I wasn’t my thoughts and needed to ignore the ones that didn’t serve me.

The plane was completely silent as we prepared for takeoff. The air felt heavy with tension as nervous energy radiated throughout the main cabin. I needed to liven up the atmosphere. If we were all going to die from this virus, we might as well go out smiling. I attempted to flirt with an Ethiopian flight attendant while using the survival Amharic I had learned a year before while cycling across her country, but my attempts were met with a scowl protruding through a masked face. They usually loved it whenever I raved about how much I adore Ethiopia in Amharic. Not this time.

A few minutes later, a heavyset man wearing shorts, a T-shirt, and a blue baseball cap plopped himself down two seats next to me. A KF-94 mask covered his face. This guy had to be an English teacher in Korea, why else would he have a mask like that? I thirsted for conversation and someone to share the uncertainty and nerves with and decided he would be the one.

“Hey. Do you speak English?”

“Yeah. I do,” he said while staring straight ahead, avoiding eye contact.

“Where are you from?”

“The United States,” he said in a monotone voice.

“Oh, great. So am I. How was your vacation? Where did you go?”

“Madagascar,” he said, eyes still avoiding me.

“Wow! That sounds amazing! How was it?”

“Yeah. It was good.”

“I would love to go there sometime! By the way, are you going to South Korea?”

“Yes. I am,” he answered abruptly. By this time I wondered why he was acting so cold and giving me one-word answers. Perhaps this was his way of dealing with the unknown of heading back to a virus-ridden land.

“Which part of Korea are you going to?”

“Daegu,” he said, finally looking at me with fear-stricken eyes. That was it. The outbreak epicenter that appeared in the world news every day. He was heading to the eye of the storm. I probably would have been shaken up if I had to walk down the contaminated city streets of Daegu.

“Yeah. My university is making me come back, even though we won’t be starting for a few weeks. I am not happy about that.”

“Oh…Your university is making you come back?”

“Yeah.”

I decided I would leave him to his thoughts since he didn’t seem willing to engage in small talk. I pulled out my book and silence ensued for the rest of the ride. No talking. No room for humor or socializing. I kept my germs and thoughts to myself.

I returned to my apartment in Seoul as the numbers continued to climb. I became stronger and more energetic as the fourteen-day incubation period after the plane ride passed. Expats living in South Korea fled the country left and right, fearing for their lives. South Koreans were furious at their government for allowing Chinese people to enter the country and several bars and restaurants even put up signs saying “no Chinese people allowed.” It seemed like I was in the worst place in the world until the rest of the world exploded with the virus at a much faster pace.

Korea has kept all of its restaurants and stores open amidst the entire pandemic season. High testing rates, contact tracing, and universal acceptance of masks have many considering it a model example as I type these words in September. It is difficult to find someone without a mask on their face in the streets of Seoul.

If there was a lesson learned throughout this entire experience, it is that you never know how things will end up in life. One moment you get on a plane to travel to a place the entire world labels as virus-ridden and dangerous. Several months later, that same place is the envy of the world. The whole situation is completely out of my control, as I can’t influence government policy nor whip up a vaccine in my studio apartment. If I would have opted to stay in Kenya a few more weeks, then I probably would have had to confront the virus in Nairobi. Perhaps the number of infected people living in Kenya simply weren’t able to be traced and documented. Where would I be better off?

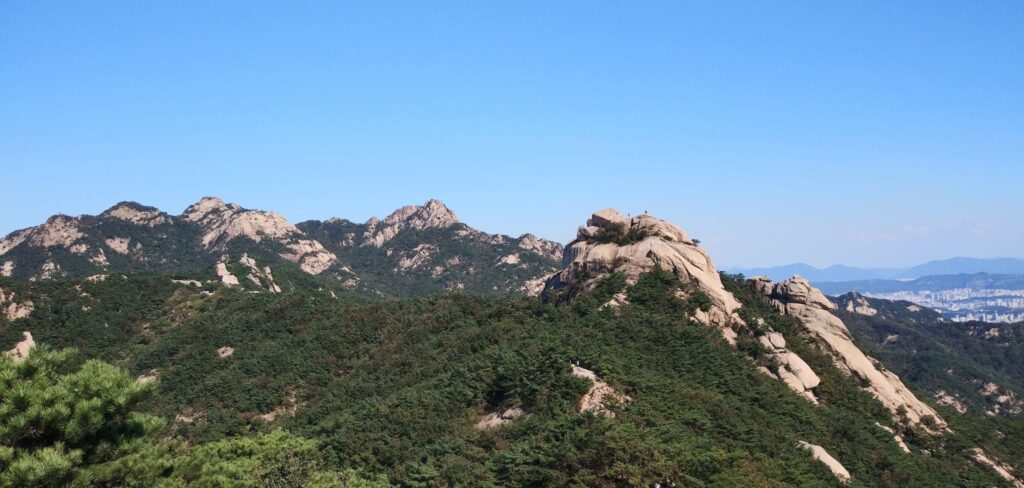

Despite all the chaos, I am free to do all the activities that made me fall in love with South Korea. I can go to the local fermented bean paste soup shack for a home-cooked meal. I can take a bus across the country and visit thousand-year-old Buddhist temples while being showered by cherry blossom leaves tumbling in the wind. I can take a bullet train to the sea and listen to the waves rustle and crash on the sandy shore.

Seven months have passed since I returned to the place Bengali poet, author, and songwriter Rabindranath Tagore referred to as the Land of the Morning Calm. I can’t wait for the day to come when I can look back at this moment in a few years and know I did everything possible to combat the spread of the virus. It is so simple. Stay home and wear a mask whenever you leave the house.

Staying at home in my single room apartment while reading, writing, and teaching sends me sailing in a sea of knowledge, creative expression, while making a positive impact on young minds. I am free amid self-imposed quarantine. So many stories need to get onto the page. So many books are out there waiting for me to devour. So many students are waiting for the tools to become stronger versions of themselves. The three activities are all interconnected. The more knowledge and wisdom I am armed with, the better educator and global citizen I will become. I relish this opportunity to come out stronger, wiser, and armed with new skills I pound into myself every second I spend in my box-sized, furniture less home.

True freedom is inside of you and is not determined by which place can eat at and what options you have for entertainment. Being stuck on the idea that you can’t go to the movie theater or eat at your favorite restaurant with your friends is nothing more than mental slavery. Slavery arises from not being able to sit alone with yourself while doing absolutely nothing.

In the West, solitary confinement is referred to as a torture mechanism. However, many spiritual teachers across Asia are convinced that being alone for extended periods of time while doing absolutely nothing is the path to true freedom and liberation from suffering. The free person is content despite any situation the world throws at him or her. The free person views solitary confinement as an opportunity to become more enlightened and cultivate a higher level of self-awareness while freeing herself or himself from the self-imposed shackles of the mind. Use this time to elevate your inner sense of freedom to levels that transcend everything that you thought was previously true.

Freedom, love, silence, truth, enlightenment, the ultimate flowering of your being – all are available to you. The hindrances just have to be removed.